At about 9 a.m. most days, Sharon Harvey unlocks an uninteresting wooden door in an alley downtown, climbs down a steep and wobbly metal staircase and starts her day as the last employee of the Allied Manufacturing Company.

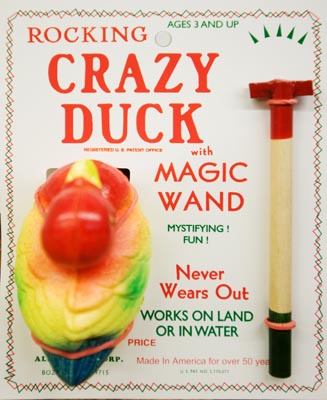

AMC was founded in the 1950s by Bozeman’s notoriously secretive businessman William J. Sullivan. The factory makes two products, both invented by Sullivan: a jeweler’s solder called Tix and Crazy Ducks, a magnetized novelty that has been sold by the millions since 1956.

Harvey, 68, has worked for AMC since 1959, when she was a high school senior. She started there to earn extra money to help her family. Over the decades, she worked her way up the AMC ladder through experience and attrition.

Even though she’s the only employee, Harvey calls herself simply the manager. She attributes her longevity to her ability to get along with the often-cantankerous Sullivan, who died in 2000.

“He was a devil. People didn’t like him,” Harvey said. “He was so smart. He’d tell other people how smart he was and how stupid other people were.”

Sullivan was something of a genius with magnets, radios and electricity. When Franklin Roosevelt came to Montana during the 1940s to dedicate the Fort Peck Dam, Sullivan set up a massive sound system to broadcast the event.

Over the years, Sullivan invented radios, burglar alarms, water leak detectors and many of the machines still used at AMC, Harvey said.

“It was just a fascination for him,” she said. “Once he put something together and saw that he could do it, he just forgot about it.”

Many of Sullivan’s inventions still litter the factory, stuffed into the basement’s hundreds of cubbyholes, nooks and crannies.

The place is a virtual museum to Sullivan’s innovation. At the far end of the basement is Sullivan’s old office, where his desk looks like it hasn’t been touched since the Chronicle last did a story on him in 1983. In that office is a shelf loaded with Sullivan’s one-of-a-kind, mostly magnetic, products.

Of course, Sullivan’s most popular invention was the Crazy Duck. Each yellow duck is made in a steam-powered, injection-molding machine designed and built by Sullivan. The machine turns tiny plastic pellets into floating ducks. Harvey then inserts a magnet into the bottom that interacts with a magnetized “magic” wand, making the duck move, well… crazily through the water.

In 1983, Sullivan told the Chronicle that he turned down an offer from Walt Disney to buy out the trademark on the Crazy Duck just six months after it hit stores.

These days, the ducks retail for $5 to $6 in tourist traps and souvenir shops from California to Vermont, Harvey said.

“They can’t sell them for much more than that because they’re what you call a junk item,” she said. “But they’ve been a good junk item for about 50 years.”

Harvey has kept AMC going part time for the 10 years since Sullivan died. She works four hours a day and spends the rest of her time at her ranch or golfing, snowmobiling or taking trips.

“We had actually planned to close it up and sell the building back when the economy was good,” she said. “[The economy’s] what’s really kept us down here.”

The company makes most of its money on the Tix solder. The ducks are too labor intensive, she said.

“I was going to quit making them a few years ago,” Harvey said. “There’s no profit in them anymore.”

Demand from her customers kept her in the Crazy Duck business though. They couldn’t imagine not having them in their shops, she said.

So Harvey keeps at it, molding, painting and packaging ducks and making solder and flux in AMC’s secluded basement, just as she has for more than since the company moved there in 1976.

The lack of daylight has never bothered her, she said.

“You look at office buildings in federal buildings and courthouses and other big buildings, they have little cubicles,” she said. “They can’t see out either.”

AMC was always known for allowing its employees flexible schedules, which meant it employed a lot of college students over the years. Harvey still treasures that flexibility.

“The reason it’s been rewarding is because I love my independence,” she said. “I can pick up and go if I want.”

Got an idea for an unusual or out-of-the-way story? Let Michael Becker know at 582-2657 or becker@dailychronicle.com.

Â